Fossil fuels provide about 80% of the world’s energy and, despite dire predictions since the early 20th century, supplies will not run out any time soon, according to speakers at a AAAS discussion on meeting global energy demand.This is an extraordinarily ill-thought out set of statements.

“Oil is good for 50 years at current consumption rates, [and] could be extended longer as you go to more difficult resources,” said Steven E. Koonin, under secretary for science at the U.S. Department of Energy. “Coal—there are hundreds of years.”

Friday, December 3, 2010

Fossil Fuels, Strange Arithmetic

I'm a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). I've been disappointed by AAAS's silence on the issues of hydrocarbon decline. In one of the email bulletins they send out, they had a link to a panel discussion on energy. Here are the opening two paragraphs--

Monday, November 15, 2010

Evolved to Run

Recently, I had occasion to read the best-seller Born to Run. I decided I needed to read the book when an acquaintance began describing the contents. He talked about events I was a part of, since I've run with the Raramuri (Tarahumara) Indians in the Leadville 100 mile run. While the book was a mixed bag, it makes some good points that are relevant to our current situation and our future.

Shortly after I acquired the book, I learned Micah True, one of principal figures in the account, was scheduled to give a talk at a local running shop. I attended and enjoyed the evening. From what I heard, running has declined amongst the Raramuri as roads and vehicular transport has penetrated to their villages. The Raramuri have a history of putting on races that pit village against village. Top runners are higher-status members of society. Yet even so, easier modes of transport stop the running.

Likewise for our society. Despite all the evidence that high levels of activity and exercise have enormous physical and mental benefits, most people will take advantage of labor-saving devices and transport. And even among the fit, most transport uses internal combustion vehicles, not feet or bicycles.

So I'm very curious to watch the reaction and evolution of behavior as it gets more and more expensive to use vehicles. Since so many of us are in dug into a hole of poor fitness and excessive weight due to inactivity, digging out will be difficult.

Shortly after I acquired the book, I learned Micah True, one of principal figures in the account, was scheduled to give a talk at a local running shop. I attended and enjoyed the evening. From what I heard, running has declined amongst the Raramuri as roads and vehicular transport has penetrated to their villages. The Raramuri have a history of putting on races that pit village against village. Top runners are higher-status members of society. Yet even so, easier modes of transport stop the running.

Likewise for our society. Despite all the evidence that high levels of activity and exercise have enormous physical and mental benefits, most people will take advantage of labor-saving devices and transport. And even among the fit, most transport uses internal combustion vehicles, not feet or bicycles.

So I'm very curious to watch the reaction and evolution of behavior as it gets more and more expensive to use vehicles. Since so many of us are in dug into a hole of poor fitness and excessive weight due to inactivity, digging out will be difficult.

Monday, September 6, 2010

Getting Nowhere and Missing the Train

We spend a lot of our time in U.S. National Parks. In fact, just this morning I did a 5+ mile run in one a few minutes from my house. Our vacations tend to center around trips to national parks. I've lost count of the number of times I've been to the bottom of the Grand Canyon--

The junction of South Kaibab, N. Kaibab and Bright Angel trails.

I've been on all, many times.

However, most of the big famous parks are literally in the middle of nowhere. How do you get there? It turns out that the existence of, and access to, at least some of the national parks is intimately linked to the interests of American railroad companies in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Friday, August 6, 2010

Pod People

It occurred to me awhile back that I should experiment with food crops that make sense for the desert. Since I have a yard full of mesquite trees and mesquite pods are supposed to be quite edible, that seemed like a good starting place. See what I mean?

That's a flowering agave in the foreground, but notice lots of mesquites behind it? The native mesquite around here is Prosopis velutina. Well, I'm getting a lesson in the uncertainties of agriculture. We had a cool spring and lots to plants, including mesquites, had a delayed flowering. No problem, I thought. I talked to my horticulturist friend Gene while I waited. He said that nutritional quality of pods varied widely. Pods with reddish highlights are supposed to have a higher sugar content.

Thursday, July 1, 2010

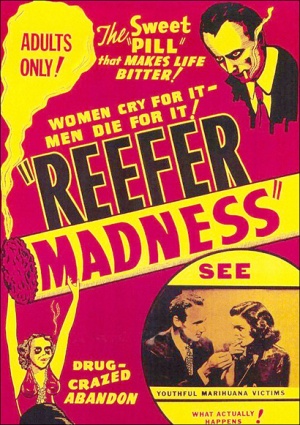

Is Oil Reefer Madness?

How many times have you heard someone talk about "our addiction to oil"? I'm getting a bit tired of it.

Physiological addiction occurs when you consume a pharmacologically active substance such as opiate narcotics, alcohol, nicotine, or caffeine in sufficient quantities with sufficient regularity that you crave the substance and have withdrawal symptoms if you don't get the compound often enough and in sufficient quantity. Once past the withdrawal phase, your body and brain may not need the substance and may function better. The tetrahydrocannabinol (THC in marijuana) referenced in the famous poster from the pot exploitation film Reefer Madness may actually be less dangerous and more beneficial than some of the other addictive substances. I leave that to the reader to decide...

None of this is true of oil. Oil is like air--we need it to function and there's no good alternative. The United States consumes more than any other nation. We could probably consume less and still maintain the world's highest Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and our economic and military dominance. But not a lot less without big changes. Morgan Downey has a great interactive graph on his blog, scarcewhales which he hasn't posted to in a while, unfortunately. He's busy on other projects. What you'll see on that graph is pretty strong evidence that America's oil consumption per person has overall risen much less than many other nations in the world. We've also maintained our position as the nation with the highest per capita GDP.

I would suggest that we are the world's dominant power precisely because we consume and process more energy from oil and other sources than any other nation. We convert that energy into a fabulous array of goods and services, incredible air and land transportation systems, and a military machine that can project all over the globe at a moment's notice.

If that's an addiction, it's tough to overcome. Since we don't have much choice as oil supply tightens, I'd very much like to see us using the power and wealth we now possess to leverage new energy sources, transmission systems, and transportation infrastructures so that we can maintain as much as possible. I'd also like to see as many as you as possible out of your cars and planes so that we can save as much oil as possible for the tractors, mining trucks, trains, and jets that support all the things we need and use. We should our feet, bodies, and brains more. The real addiction is to inactivity. A fit population would feel better, work harder and smarter, and produce more value.

Any chance I'll see a few more folks on my bike rides to work soon???

Tuesday, June 22, 2010

Growing Fuel? Not with food crops.

Notice I'm not piling on and writing about the Gulf Oil Spill. It is worth noting in passing that even if the spill amounts to several million barrels over several months, that will still only come to a tiny sliver of the world's 85 million barrels per day of consumption. And that ties to my real topic for this post.

I asked a friend of ours who studies the world food supply how much food in calories the world produces. Joel sent me some numbers and a recent report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

In 2009, the world produced 2.2 billion metric tons (mt) of cereal grains, 0.4 billion mt of oil seeds, 0.16 billion mt of sugar, 0.29 billion mt of meat, and 0.14 billion mt of fish. Since most of the meat was made by feeding the cows and pigs the cereal grains, lets drop those out. And I'm skipping dairy, since it's mostly water. So the world produced about 2.9 billion mt of food in 2009. I wondered how much of that is usable energy. A study I came across at the University of Florida, puts the metabolizable energy in wheat, corn, and soybeans all at about 1500 calories per pound. Since those grains make up the biggest share of the 2.9 billion mt, that gives us a ballpark figure of 9.57 quadrillion calories produced in 2009. A barrel of oil has approximately 1.39 million calories of energy. So at about 31 billion barrels of oil a year st current rates of consumption, that's 43 quadrillion calories of oil per year.

That means there's over 4 times as much energy in the oil we burn in a year compared to the food we grow in a year. Can we expect ethanol produced from food crops like corn or even sugar cane to provide a significant fraction of our transportation energy requirements? David Pimental, a respected ecologist at Cornell University, has performed extensive analyses of biofuels, especially corn. He summarized his work last year in the Harvard International Review. You should go read the article for yourself, but he calculates that if all the corn grown in the U.S. in a year could be made into corn ethanol, it would provide only 4% of our energy consumption. But that's not taking into account the whole energy budget, I think. Last year, we used 33% of our corn production to produce 9 billion gallons of ethanol, which only has about 2/3 the energy of gasoline. The works out to the equivalent of 143 million barrels of oil, which sounds decent. However, since the most optimist estimates of the amount of energy put into corn versus energy back is 1.3 to 1, that means we burned 109 million barrels of oil to get the corn ethanol. That leaves 34 million barrels of oil equivalent. The U.S. uses 20 million barrels of oil per day. So we used 1/3 of a year's corn crop to produce slightly less than a 1.5 days of transportation energy. Using all the corn would only give us 1.3% of our energy needs for the year.

Obviously, trying to pour our food into our gas tanks won't get us very far.

I asked a friend of ours who studies the world food supply how much food in calories the world produces. Joel sent me some numbers and a recent report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

In 2009, the world produced 2.2 billion metric tons (mt) of cereal grains, 0.4 billion mt of oil seeds, 0.16 billion mt of sugar, 0.29 billion mt of meat, and 0.14 billion mt of fish. Since most of the meat was made by feeding the cows and pigs the cereal grains, lets drop those out. And I'm skipping dairy, since it's mostly water. So the world produced about 2.9 billion mt of food in 2009. I wondered how much of that is usable energy. A study I came across at the University of Florida, puts the metabolizable energy in wheat, corn, and soybeans all at about 1500 calories per pound. Since those grains make up the biggest share of the 2.9 billion mt, that gives us a ballpark figure of 9.57 quadrillion calories produced in 2009. A barrel of oil has approximately 1.39 million calories of energy. So at about 31 billion barrels of oil a year st current rates of consumption, that's 43 quadrillion calories of oil per year.

That means there's over 4 times as much energy in the oil we burn in a year compared to the food we grow in a year. Can we expect ethanol produced from food crops like corn or even sugar cane to provide a significant fraction of our transportation energy requirements? David Pimental, a respected ecologist at Cornell University, has performed extensive analyses of biofuels, especially corn. He summarized his work last year in the Harvard International Review. You should go read the article for yourself, but he calculates that if all the corn grown in the U.S. in a year could be made into corn ethanol, it would provide only 4% of our energy consumption. But that's not taking into account the whole energy budget, I think. Last year, we used 33% of our corn production to produce 9 billion gallons of ethanol, which only has about 2/3 the energy of gasoline. The works out to the equivalent of 143 million barrels of oil, which sounds decent. However, since the most optimist estimates of the amount of energy put into corn versus energy back is 1.3 to 1, that means we burned 109 million barrels of oil to get the corn ethanol. That leaves 34 million barrels of oil equivalent. The U.S. uses 20 million barrels of oil per day. So we used 1/3 of a year's corn crop to produce slightly less than a 1.5 days of transportation energy. Using all the corn would only give us 1.3% of our energy needs for the year.

Obviously, trying to pour our food into our gas tanks won't get us very far.

Thursday, May 6, 2010

Post-Roundup World

Donny hit Send just as the WiFi shut down as the sun dropped and the farm's solar panels stopped working. The Ωmail service some former Googlers had built with the wreckage of Gmail after Google folded wasn't free, but it was the best way to keep in touch with his wife back in the city. He, Fred, and 4 other guys had come here in Fred's Prius because Fred had learned there was a farmer with WiFi in the dorms who hired city workers, albeit not for the same pay as the more experienced latino workers. The immigrant latinos weren't coming up nearly as much since the economic collapse in the U.S. They had been able to carry enough gas in the Prius to get to the farm, but weren't as sure about finding gas on the way home over the deteriorating roads at the end of the season. Donny locked up his iPad in his locker and got into bed. He thought for a few minutes about the uselessness of his Ph.D. in Economics, but the hard work tilling, planting, and pulling weeds was better than the sporadic dole in the city. The farmer paid his wages directly into PayPal, which had managed to stay in business and take over some of the functions that the failed banks once performed. The handful of remaining banks only troubled themselves for what passed for wealthy in America's shrinking economy. The farmer numbered amongst those wealthy few. He had bought up several of his failed neighbors and had enough cash to pay for human workers, since machines were now too expensive to run. Donny thought wistfully about his wife and kids, and of the oil-rich world of his youth, when life was easy and people weren't starving back in the city, but exhaustion quickly put him to sleep.

Saturday, May 1, 2010

Where's Your Beef Been?

Recently, the Population Reference Bureau and the International Food Policy Research Institute hosted their first "Malthus Lecture". A distinguished researcher we know spoke on Meat. How's that for a title? This follows on the heels of a special issue of Science Magazine devoted to Food Security. I subscribe to Science and I looked at outline of the lecture as well as the web sites of the food organizations. With the world's oil production on the verge of a 4-5% annual decline, one would think there would be some discussion of effects on food supplies and human populations, but there's not. Why is this?

Let's lead into this with my experiences with the iconic meat animal, the cow. I go way back with cows.

Cattle ranching is a ubiquitous feature of the American Southwest. All my field work as an undergraduate and a doctoral student was on range I shared with cows. We're within running distance of a large ranch where we routinely hang out with cows, and my wife has photographed the round-up. She's helped with a round-up on horse-back on another ranch. This shy girl was photographed in the arid Owens Valley in California on my way to the Death Ride.

Let's lead into this with my experiences with the iconic meat animal, the cow. I go way back with cows.

Cattle ranching is a ubiquitous feature of the American Southwest. All my field work as an undergraduate and a doctoral student was on range I shared with cows. We're within running distance of a large ranch where we routinely hang out with cows, and my wife has photographed the round-up. She's helped with a round-up on horse-back on another ranch. This shy girl was photographed in the arid Owens Valley in California on my way to the Death Ride.

Monday, April 19, 2010

Offshore Drilling and Arithmetic

Ok, I'm playing catch-up. I've been otherwise occupied with other interests and psychotic computers. But the recent plan by the Obama administration to open new areas to offshore oil drilling is provocative on several levels.

Oil wells are inherently messy and potentially damaging to the environment. Nothing much can eat the oil, and oil makes life tough for creatures that encounter it. Might have something to do with why petroleum has stayed stabile over geologic time scales. There are some bacteria living at the bottom of Lake Baikal that seem to eat oil. Since Baikal is the deepest lake in the world the bacteria probably can't be too choosy down there. Correction--Reading about the Gulf oil spill indicates lots of bacteria in the ocean seen to eat oil. It's painfully apparent that by no means all the oil gets eaten, however.

Unfortunately, we aren't going to do too well in the short term without oil to burn. Over on my companion website, I'm trying to document the shortfall. It's hard too see how we can cushion the decline in oil production from the good established fields that are declining around the world without some new production.

That's said, let's be realistic about what can be obtained by the new areas being opened up. The New York Times article about the plan reports the Interior Department claims there could be "as much as a three-year supply" of oil in the area being opened to exploration. The only actual figures quoted are "as much as 3.5 billion barrels of oil in the eastern Gulf of Mexico, "the richest single tract". Assuming we could achieve the maximun practical recovery from a field of 70% of the oil, that's 2.45 billion barrels recoverable. At the current U.S. consumption rate of about 20 million barrels per day, that's a 122.5 day supply, which isn't quite 3 years. In another article in Bnet report the areas around Alaska could amount to 19 billion barrels, which sounds more substantial. Applying our arithmetic, that works out 665 days for a total of 787.5 days, which is a bit over 2 years. And that's assuming we keep it for ourselves...

Oil wells are inherently messy and potentially damaging to the environment. Nothing much can eat the oil, and oil makes life tough for creatures that encounter it. Might have something to do with why petroleum has stayed stabile over geologic time scales. There are some bacteria living at the bottom of Lake Baikal that seem to eat oil. Since Baikal is the deepest lake in the world the bacteria probably can't be too choosy down there. Correction--Reading about the Gulf oil spill indicates lots of bacteria in the ocean seen to eat oil. It's painfully apparent that by no means all the oil gets eaten, however.

Unfortunately, we aren't going to do too well in the short term without oil to burn. Over on my companion website, I'm trying to document the shortfall. It's hard too see how we can cushion the decline in oil production from the good established fields that are declining around the world without some new production.

That's said, let's be realistic about what can be obtained by the new areas being opened up. The New York Times article about the plan reports the Interior Department claims there could be "as much as a three-year supply" of oil in the area being opened to exploration. The only actual figures quoted are "as much as 3.5 billion barrels of oil in the eastern Gulf of Mexico, "the richest single tract". Assuming we could achieve the maximun practical recovery from a field of 70% of the oil, that's 2.45 billion barrels recoverable. At the current U.S. consumption rate of about 20 million barrels per day, that's a 122.5 day supply, which isn't quite 3 years. In another article in Bnet report the areas around Alaska could amount to 19 billion barrels, which sounds more substantial. Applying our arithmetic, that works out 665 days for a total of 787.5 days, which is a bit over 2 years. And that's assuming we keep it for ourselves...

Thursday, March 4, 2010

The Oil Crunch; The ITPOES Report

The second report of the UK Industry Taskforce on Peak Oil & Energy Security was released last month. Richard Branson, Virgin Group's founder is one of the members, and was in the news regarding the report. People can download it from their website--http://peakoiltaskforce.net/. I read through it, 60 pages, although I skimmed some of the appendices. This might be the best recent analysis I've read, although I admit I've only skimmed the IEA's reports, which I think soft-pedal the situation.

The report has quite a bit of supporting information relative a projected oil production plateau of 92 million barrels per day. This is significantly higher than the 89 million b/d I've seen claimed by Morgan Downey and others. If true, this puts the point at which demand intersects with production (their "oil crunch") out a few years, rather than happening within the next year. Same effect, but a bit further in the future.

The report has quite a bit of supporting information relative a projected oil production plateau of 92 million barrels per day. This is significantly higher than the 89 million b/d I've seen claimed by Morgan Downey and others. If true, this puts the point at which demand intersects with production (their "oil crunch") out a few years, rather than happening within the next year. Same effect, but a bit further in the future.

Monday, February 8, 2010

Problematic Prius (Prii?)

What's the plural of Prius? If it's like cactus, it should be Prii. Regardless, they're included in Toyota's string of issues and problems. This seems like a good time to discuss the technology and it's limitations.

I purchased a Prius last March when my Echo started to eat it's transmission. It had had a hard life. I looked around and realized that the Prius was practically the only vehicle that got better gas mileage than the Echo. Thanks to the recession, they were easy to purchase. I've really enjoyed mine, although the lack of gears to shift was an adjustment. I routinely get over 50 mpg.

I purchased a Prius last March when my Echo started to eat it's transmission. It had had a hard life. I looked around and realized that the Prius was practically the only vehicle that got better gas mileage than the Echo. Thanks to the recession, they were easy to purchase. I've really enjoyed mine, although the lack of gears to shift was an adjustment. I routinely get over 50 mpg.

Wednesday, February 3, 2010

Irony Gap

Sunday my trail running group staged a run over the Charoleau Gap, a pass over the San Maniego Ridge. This route is a well known jeep trail. I brought up the rear taking photos. The turnaround was at the first crossing of the Canada del Oro, which drains the valley between San Maniego and Oracle Ridge--

That was about 9.7 miles into the run. On the way back as I neared the Gap, I started to encounter 4 wheel drive vehicles--

That was about 9.7 miles into the run. On the way back as I neared the Gap, I started to encounter 4 wheel drive vehicles--

Wednesday, January 27, 2010

Ratios, first post

In my essay (see the Oil1859 website), I talk a bit about return ratios. I need to elaborate on that concept, because it's fundamental to understanding the elaborate structure of modern industrial societies. In pre-industrial societies that depend on people and animals performing labor to produce food, raw materials, and finished products, not much complexity is possible. A bit more complexity is possible when you can use wind or water energy to operate simple machines and sailing vessels.

The basis of the industrial revolution was coal. A generation of machines was devised that burned coal to heat water into steam; the steam engine. Societies grew more layers and got more complex. I don't know what the return ratio was for digging up coal and burning it, but I'm sure it was intermediate between the return ratio of horses and the 15 to 1 return ratio of oil production. The cornerstone of modern societies is electricity which powers all manner of machines attached to the electrical grid and oil-based fuels which power almost everything not attached to the grid. The electricity is mostly produced by burning coal and natural gas, but digging up the coal and drilling the gas wells depends mostly on machines that burn petroleum fuels. So the return ratio on oil production affects everything else.

To bring this back to society, look around you and ask yourself how many people you know that actually grow, mine, or make something. Not many, probably. My home state Arizona had about 2.855 million people at work at the end of 2009. Arizona is the country's major copper producer and a significant source of timber, yet only 10,800 people are employed in mining and logging. I've been told 7000 of those are miners. That's only possible because mines depend on enormous oil-powered machines to dig and move the ore, controlled by a relative handful of people. This in a state where most people worked in mines at the beginning of the 20th century. 159,000 people work in manufacturing jobs, and 132,00 people work in constuction. 443,500 people work in agriculture because Arizona is a huge agricultural exporter. So that's 745,300 people you could argue produce something. In contrast, 2,109,500 people work in service sector and transportation jobs. Cheap oil allows a huge superstructure of "service economy" to be built on a small base of producer jobs. As the cost of oil rises, the effect will be twofold. People will spend less money on nonessential goods and services. Human labor will become more valuable relative to fuel costs (no more weed-whackers...).

So how will the job structure shift as the service economy deflates? More people will be probably be needed to grow food if there are fewer machines in the fields. Will there be pickaxes in mines again? Who will start the companies to do the work and how will they get the money to pay people? A plan or two would be helpful.

The basis of the industrial revolution was coal. A generation of machines was devised that burned coal to heat water into steam; the steam engine. Societies grew more layers and got more complex. I don't know what the return ratio was for digging up coal and burning it, but I'm sure it was intermediate between the return ratio of horses and the 15 to 1 return ratio of oil production. The cornerstone of modern societies is electricity which powers all manner of machines attached to the electrical grid and oil-based fuels which power almost everything not attached to the grid. The electricity is mostly produced by burning coal and natural gas, but digging up the coal and drilling the gas wells depends mostly on machines that burn petroleum fuels. So the return ratio on oil production affects everything else.

To bring this back to society, look around you and ask yourself how many people you know that actually grow, mine, or make something. Not many, probably. My home state Arizona had about 2.855 million people at work at the end of 2009. Arizona is the country's major copper producer and a significant source of timber, yet only 10,800 people are employed in mining and logging. I've been told 7000 of those are miners. That's only possible because mines depend on enormous oil-powered machines to dig and move the ore, controlled by a relative handful of people. This in a state where most people worked in mines at the beginning of the 20th century. 159,000 people work in manufacturing jobs, and 132,00 people work in constuction. 443,500 people work in agriculture because Arizona is a huge agricultural exporter. So that's 745,300 people you could argue produce something. In contrast, 2,109,500 people work in service sector and transportation jobs. Cheap oil allows a huge superstructure of "service economy" to be built on a small base of producer jobs. As the cost of oil rises, the effect will be twofold. People will spend less money on nonessential goods and services. Human labor will become more valuable relative to fuel costs (no more weed-whackers...).

So how will the job structure shift as the service economy deflates? More people will be probably be needed to grow food if there are fewer machines in the fields. Will there be pickaxes in mines again? Who will start the companies to do the work and how will they get the money to pay people? A plan or two would be helpful.

Monday, January 25, 2010

"10 Pieces" Decade Overview: USGS Hiding, IEA Fudging

This is a short article that seems to be a listing of what Steve Andrews considers important factors and developments of the past decade--http://www.aspousa.org/index.php/2010/01/top-10-pieces-of-the-peak-oil-puzzle-during-the-2000s/. Two of his "pieces" in particular shed light on topics I had wondered about. Piece 1 is the USGS World Oil Studies, that inexplicably stopped after 2000. Apparently before that they came out every 4-5 years. Then see his Piece 10, an article in the Guardian from November 2009 that reports that the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development's International Energy Agency was pressured by the US (who exactly?) to underplay the rate of oil production decline from existing oil fields. The stated justification for the pressure was avoiding a panic which would affect financial markets and damage America's access to world oil.

Unfortunately taken together, these pieces reinforce the sense that we're seeing around us is the aggregate of lots of denial. I've discussed this with my psychologist friend Brian who specializes in anger management. He thinks the dominant psychological mechanism at work in our society relative this issue is denial. When forced to deal with the problem directly, the natural tendency for people in denial is to become angry, followed by depression and a sense of hopelessness. Not very productive reactions.

As with the financial crisis (which was triggered by the first spike in oil prices), denial until the situation deteriorates to the point of collapse guaranties a much worse collapse when it comes. Along these lines, I read a couple of days ago in Morgan Downey's blog that American cars buyers are no longer considering fuel economy as a top factor in vehicle purchase despite the recent history of high fuel costs. Actually, in my experience, many people claim lack of knowledge of the prospect of oil decline, although part of the denial mental mechanism can be not attempting to investigate a topic if you're afraid you might learn something unpleasant. Brian thinks he'll need to put on workshops for depressed, angry people when denial no longer works. He may need to work pro-bono.

Unfortunately taken together, these pieces reinforce the sense that we're seeing around us is the aggregate of lots of denial. I've discussed this with my psychologist friend Brian who specializes in anger management. He thinks the dominant psychological mechanism at work in our society relative this issue is denial. When forced to deal with the problem directly, the natural tendency for people in denial is to become angry, followed by depression and a sense of hopelessness. Not very productive reactions.

As with the financial crisis (which was triggered by the first spike in oil prices), denial until the situation deteriorates to the point of collapse guaranties a much worse collapse when it comes. Along these lines, I read a couple of days ago in Morgan Downey's blog that American cars buyers are no longer considering fuel economy as a top factor in vehicle purchase despite the recent history of high fuel costs. Actually, in my experience, many people claim lack of knowledge of the prospect of oil decline, although part of the denial mental mechanism can be not attempting to investigate a topic if you're afraid you might learn something unpleasant. Brian thinks he'll need to put on workshops for depressed, angry people when denial no longer works. He may need to work pro-bono.

Saturday, January 23, 2010

Reflections on slime

There's lots of money being directed to research on algae as a source of biodiesel. ExxonMobil has committed $600 million to slime research. Closer to home, the University of Arizona has several researchers up to their elbows in algae, as described in the local newspaper. Some strains of algae are high in lipids (fats and oils) that can be extracted and burned, and what remains is high in protein, which animals can in principle eat. My impression is that algae may have a better return ratio than corn (1.3 to 1; lousy), but to make sense, it needs to approach the 15 to 1 return ratio of conventional oil. I'm trying to imagine scaling to the millions of barrels (42 gal/barrel) per day necessary to provide a credible supplement to declining conventional oil.

Friday, January 22, 2010

And now a website

The day after I wrote the paragraphs below I decided I needed an actual website to complement the blog, since I want to do web pages as well as blog posts. I don't see the equivalent of WordPress's Page function, so we'll make do.

Thursday, January 21, 2010

What is this?

I'm pretty sure we're at the peak of oil production worldwide, headed into the decline phase. Everyone alive today in advanced economies treats petroleum and the products derived from petroleum, fuels and petrochemicals, as a given. The reality is that oil is a scarce and limited resource, and we've used the bulk of what's easy and cheap to extract. I'm trying to understand the situation and make reasonable extrapolations that are useful to me and those around me.

I decided a blog was the best place to organize the thoughts that I wanted to share. We'll see how it develops.

I decided a blog was the best place to organize the thoughts that I wanted to share. We'll see how it develops.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)